Hi, my name is Leah Tharin, and this is my Substack: hot takes on product-led growth/sales and organizational scaling.

I advise companies on how to not burn everything down in the process. I run cohorts on PLG every two months; join me!

I wrote an article on the topic of why Alignment is at the heart of every great leader; it was one of my most-read articles to date:

Leadership is about leading people in a given direction, not necessarily managing them. At the heart of it is the art of creating alignment and inspiring people to move.

While I think that every manager is, to some degree, a leader, not every leader has direct reports, and IC Leadership (leading without managing people) has been a huge unlock in my career to understand that you lead more people than you manage.

In this 5 part series, I’ll dive into each one of these critical components:

Thorough Market Knowledge (This article)

Growing in front of your employees (coming soon)

Experimentation skill to learn, not succeed (coming soon)

Part 2: Market Knowledge

“Scientia potential est.”

Knowledge is power. With this quote by Sir Francis Bacon, he most likely wanted to transmit the idea that having and sharing knowledge is the cornerstone of reputation, influence, and power. (Source)

The problem we constantly wrestle with when we look at leaders is that we think the inverse is also true: Being powerful or influential somehow means that you know what you’re talking about. It doesn’t.

In the first part of my Leadership guide, I talked about how to convey a story, and one important part there is your credibility when communicating. If storytelling is your Marketing department promising a good product, then knowing what you’re talking about is the foundation it was built on.

It’s the difference between a smoke show and having actual substance.

Let’s deconstruct the phrase “Market Knowledge” in two parts:

How to gain focussed knowledge that matters → Market

How to separate the illusion of knowledge from fact → Knowledge

Market, how to focus on what matters

Through my career as a UX researcher, I learned a principle that seems to hold up in most situations:

Individuals will tell you about their motivations. Those allow you to form hypotheses that are falsifiable but, at this point, unverified.

Quantitative data that we collect afterward from above will enable us to check these hypotheses.

This might sound incredibly obvious, but we often commit the mistake of analyzing a group of people's behavior and then drawing conclusions on “why” they did something with our product.

Three different types of illusion keep us from doing this efficiently: the quantitative, the qualitative, and the leadership illusion:

The quantitative illusion

Let’s assume you are in charge of running a fitness studio. You have perfect tracking in place; you know exactly how every machine you have is being used and by whom. Your dashboards are absolutely fantastic and give you an immediate picture.

Based on this usage knowledge, you can decide whether you need more or fewer machines of a specific type. But you cannot answer a simple question:

Why does every individual work out at your studio?

You might think the answer is simple. “Well, they just want to get fit, like everyone else.”

That’s a tablestake of what makes a fitness center a fitness center after all, but it’s not a differentiator.

When you talk to people individually, you will hear different reasons mixed in:

“I want to unwind from the stress at work and home. It’s my only me-time. I like that I just have my peace here.”

“My doctor told me I need to work out to deal with a medical problem; your studio is covered by my insurance.”

“I come here because I love to be in an environment where others are pushing themselves. It motivates me to see others progress and have access to great trainers.”

“I work out with my best friend here weekly. We keep each other accountable, your studio is close to our places, and a lot of other women are training here. We like the vibe and feel safe.”

No amount of quantitative analysis uncovers these differentiators. Talking to people in a qualitative setting does.

Knowing your differentiators allows you to excel in your market. It’s the difference between having a product that retains and wows people and one that is “just doing its job.”

The qualitative illusion

We also have to deal with the other side of the same coin. No amount of interviewing individuals by itself will tell you how your market, from a macro view, behaves.

People who fall prey to this tell me often they have a superior “product sense”. I attribute this mainly to the personal cult of Steve Jobs and other prolific people in the product industry and oversimplifying their work.

I’ve worked in this industry for over two decades and it happened to me:

Getting high on your own supply.

Just because you can sell, structure, and argue well about an interview you had with an important client or individual user does not mean you are right about the conclusions you drew from it.

It is undoubtedly helpful to have a “sense” of what could be important and to look behind the curtain at what users and prospects tell you. That’s a good use of “product sense”.

But to build an entire quarterly initiative on the basis of that insight is bad product management if you could reduce the risk of being wrong beforehand.

The same goes for statements like “A lot of our users are complaining about the stability of our product” or “Our interface looks dated; it needs an update.”

Specifics, please. How big is the problem? We need to put a dimension on assumptions that create work in our organization. Otherwise, they become incomparable with other things we could do.

The road to hell is paved with the best intentions. And for product and growth leaders, they started with “It’s very obvious that…”. Even in feature factories, every single item in their bloated backlogs started with, “Oh, this is a good thing to do…”

If it’s so obvious, you should also be able to find some kind of verification for it in data easily. Sit down and think about it for at least a couple of minutes.

The rare exception: Innovation / Product Market Fit.

When we talk about innovative bets where there is absolutely no data available, yes, we can make an exception. But even for innovative bets, we expect quantitative verification, which happens after the fact but is defined beforehand:

Are there steps we can take before we build a full product to further verify our assumptions? (Painted Door tests, Wizard of Oz, etc.)

Are we ready to stop the project if those steps show that our assumption is not as strong as we thought it was? This deserves special mention because a lot of leaders are just going through step one because they have to. They still find ways to twist the results and overcommit afterward.

Define beforehand whether there are signals that automatically trigger a stoppage if you find them.

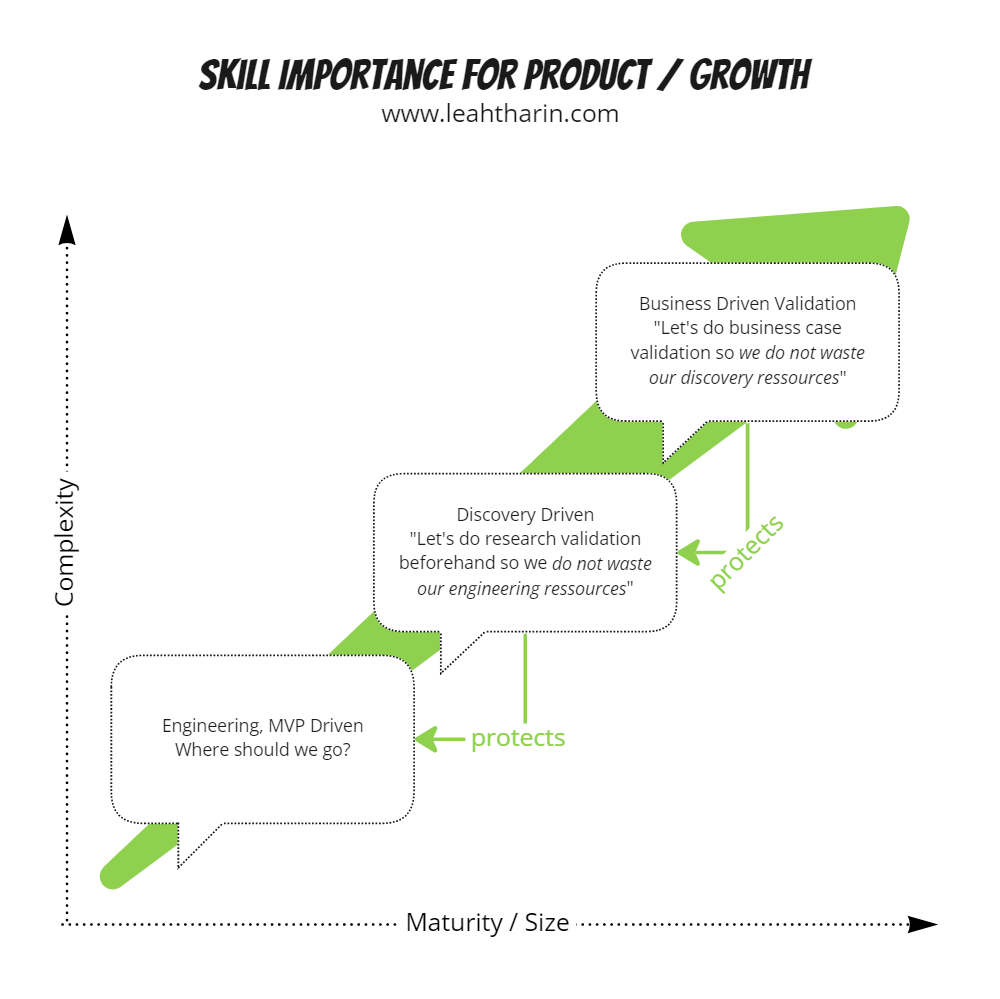

You can find an enhanced concept about resource protection in my product market fit guide under “1.2 Why no framework can guarantee success:”

The leadership illusion

One of the misconceptions I had when I was younger was that I would stop doing operative research as I climbed the career ladder. I love talking to people and figuring out why they do what they do. My love for quantitative data research came much later.

While it is true that you can outsource some parts of your research as a leader, there is one thing that has always held true for me:

Whenever I personally talked regularly to ICPs, I succeeded and had an outsized impact.

Whenever I conducted some data analysis myself, I succeeded and had an outsized impact.

Whenever I stopped talking to our ICPs or did little data querying, I had little impact.

Whenever I read board slides and user studies which contain big assumptions I take note of them but verify them later.

Do not rest on the laurels of the research of others:

Things get lost in translation all the time.

Just as you, others can and will make mistakes.

No one has the additional context you have, and you don’t have their context.

No summary of market and user assumptions can carry the context in which it surfaced in a simple sentence. Talking to people yourself and getting a “feel” for them cannot be outsourced. This is not a sign of distrust or micromanaging, it’s a reflection of the complex nature that our customers have. Opportunity lives where others don’t see it.

Still, summaries and user studies are incredibly important guides to shorten the way to your insights. And for less important assumptions in the organizations, it’s unrealistic to cross-check everything. (See later “Economic Fact Checking”)

However, you might think stories like the one from Jeff Bezos calling customer care are clickbait content, but they are very common and necessary:

If it’s easy to check something important, just do it.

I really do not care how senior the title is in your organization:

If you work in sales, marketing, product/growth, engineering, customer success or are the CEO: if you don’t talk to prospects yourself regularly your knowledge is flawed. And as a consequence the impact of your organization.

Every single good sales leader can tell you an open secret in running a successful sales organization: You do not sell in the US to high-value clients without being in the US. That’s not only because clients like to have a personal touch. It’s also because good salespeople know that their clients have some local particularities they need to know in order to close a sale. You need to “feel” your customers in order to sell to them efficiently.

If it would be possible without, sales would do it. Sales are really good at optimizing their own processes; you can believe that.

Learn with the people you guide

The knowledge you attain as a leader is the sum of your own research paired with what the people around you know.

It’s a terrible waste of talent if you assume because you are the leader that you have to know everything yourself and give knowledge to others only.

It’s very rare that I don’t cross-check my assumptions with the team around me. I might have more data at hand, but I don’t keep this data to myself to appear competent. My job is to surface; their job is to challenge me on it.

We are much more than the individual parts and people of our team. A nice side effect is also that people feel valued and are happier if they are part of the process when you form wide reaching assumptions.

Cover your weakness

Do yourself a favor and empower yourself in the area that doesn’t come naturally to you whether that’s qualitative or quantitative research.

Quantitative: I learned relatively late in my career how to write SQL and query data myself. In the age of ChtatGPT and online courses, there’s no more excuse not to be proficient in it and basic statistical analysis. Your data scientists can help you out but shouldn’t do all the work for you.

To this day, I query my own data as much as I can; it also gives you important insights into how your Growth and Product people have to work with it and the challenges they face.Qualitative: Interviewing is hard; it’s a muscle built with repetition. If you need a good frame of how to get started, learn how to perform switch interviews. If you can shadow salespeople, do it. They are some of the best context researchers you have in your organization. Don’t be afraid to ask your UX researchers how to conduct interviews; they are also experts in what to avoid.

Tactical tips on how to get started with research from a higher level:

Read quarterly reports from your competition; there are good assumptions about market developments if you look for them that you can verify and use as talking points afterward.

Job adverts for high-level positions with important players give you an indication of what they bet on. These are good starting points to verify later.

Don’t overfocus on your own customers. It’s good to have a healthy mix with ICPs that are not yet in your inbound. When I worked at Jua (Weather predictions) I chatted with meteorologists and power traders that were not in our inbound.

We have more and more great AI tools to check assumptions. Perplexity.AI is an incredible language model that helps you find knowledge and links the related sources. Don’t fall into the trap, though, to just confirm what you believe with them. It’s about finding diverse sources that you were not aware of.

Market reports. Some market reports are quite expensive, but you’ll notice that it can actually be worth it to spend a couple thousand $ for a good one. Ask other leaders in the same field whether they know good ones. They are usually coming from the same companies. I had some good success with Forester and other big-name brands. They are becoming increasingly important if you are involved in yearly forecasting for bigger budgets. Still, they are a starting point, not the end.

Outcome Driven Innovation. To this day, my favorite method to combine qualitative and quantitative insights meaningful for product teams. See 3.4 of my PMF guide

User your own product, regularly. Make people around you use it. Regularly. Dogfooding exercises are never optional. You can’t understand your market if you don’t know what you’re selling.

Knowledge, how to separate fact from fiction

We want to of course make sure that what we believe to know is accurate. How do we separate fact from fiction?

Unfortunately, knowledge, especially in tech, lives on a spectrum. We work from assumptions all the time, and whether we “know” the truth or believe in fiction is, even in retrospect, often unknown.

To deal with this, we have to first assume there is a problem and then see whether could in fact, measure our own accuracy.

Welcome to therapy:

Step 1: I am probably wrong

There are a number of biases that play tricks on us, and they are really powerful. The more well-known ones are confirmation and hindsight bias.

While those are mentioned often and known, it’s worth understanding why we still fall prey to them:

The fear of looking unprofessional: I tell this to my cohort students all the time: if your product makes someone look unprofessional (a service going down in the middle of a presentation, etc.) in their life, you trigger all kinds of bad responses.

The same goes for knowledge. Get comfortable with the fact that just because you said something in the past or because you assume you “should” know something in your position doesn’t mean that you won’t make mistakes.

It’s a sign of seniority that you can change your opinion in the light of new facts or past misjudgments and admit to that openly.Mixing personal preferences with facts: This is an uncomfortable truth. We don’t consider certain facts because someone we don’t like is holding them. We would never admit to that to ourselves or others because that in turn would make us look unprofessional again.

Overconfidence: We tend to love ideas because we had them in the first place. This can be a mixture of not wanting to admit we are wrong or simply because we are overconfident in our abilities (and/or underestimate everyone else).

These emotional drivers have a strong hold over us. In order to not deal with them, we sometimes resort to easier-to-defend biases like the confirmation bias. We might not even be aware of them. It’s not malice. It’s just our ego protecting ourselves.

I found that honestly engaging with someone’s arguments in retrospect after some time has passed oftentimes helps. Especially if that person is draining my energy or catches me in the wrong moment.

Step 2: Economic fact-checking, choose your battles

We can use a risk management model to avoid falling prey to bias most of the time with the least amount of effort.

Obviously, the effort we spend on verifying anything should be tied to the impact it has potentially on the business. Aside from the more obvious method like stack ranking, I try to think about assumptions in the context of risks traveling downstream:

For instance, this chain of assumptions:

“Our ICPs are SMBs in Europe…”

“...and the main users for our product are directors of Marketing.”

“There are 30,000 directors of Marketing in our Market that we can reach.”

“Our newest product will address a monetizable need of these directors by generating reports they need.”

“We introduce a new subscription tier including this product and market directly starting in the next quarter.”

How much time should you spend on each assumption to ensure it’s correct? The general rule is that the earlier in the chain, the more time you want to spend on it.

If your ICPs do not live in Europe, every assumption afterward is probably also wrong. Similarly, if the users are not the directors of Marketing, the Market size will be wrong, and the product should have never been created.

Zoom out, go upstream, and challenge critical assumptions that feed into your work. Even if you are “just” a product or growth manager, it’s important that you understand the assumptions that created the need for whatever you’re working on.

There’s no question, though, if you are the CPO in the above example, then ICPs are your responsibility.

To check your knowledge and assumptions sufficiently, you should outsource some of the knowledge checking to your direct reports; the more downstream an assumption is, the more likely you should trust someone else with it.

Only if you free up this time will you focus on what matters: The upstream risk. That’s why trusting the people you lead is not just nice to have but crucial.

Your resources are limited. Choose your battles.

If you as a leader obsess too much about details, not only will you be resented for it because you talk into the work of others, but you will also miss the bigger picture which the people you lead also can’t see.

Step 3: Treating knowledge as predictions

Our knowledge about our markets is fundamental to what we do because we are leading the people around us to a point in the future, not the present.

A product we build for two years is built on the assumption that the needs it serves are still present in two years. We build for the future.

In their amazing book “Superforecasting” Philip Tetlock and Dan Gardner outline what sets a good forecaster apart from a bad one. He calls them super forecasters:

Break down problems into smaller, more manageable parts: Superforecasters don't approach a prediction as a single, monolithic challenge. Instead, they break down the question into smaller pieces and analyze each component separately. This method, often referred to as "Fermi-izing" after the physicist Enrico Fermi, who was famous for his ability to make accurate estimates using such breakdowns, helps in making the problem more tractable and the forecasting process more systematic and analytically rigorous.

We commonly use this in tech interviews when we ask candidates questions like: “How many windows are in San Francisco?”Embrace probabilistic thinking: One of the hallmarks of superforecasting is the ability to think in terms of probabilities rather than absolutes. Superforecasters assign confidence levels to their predictions, reflecting the degree of uncertainty. This approach acknowledges that the world is inherently unpredictable and that few outcomes are ever 100% certain. By updating their predictions as new information becomes available, superforecasters can adjust their forecasts to reflect changing circumstances, which is a practice known as "Bayesian updating."

I use this with product organizations when we plan quarterly initiatives. People have to state beforehand how certain they are they can reach each individual goal. This allows you to check afterward the accuracy and whether a team is over or under-confident to train probabilistic thinking.Actively seek out information and diverse perspectives: Superforecasters are voracious learners who actively seek out a wide range of information sources, including those that challenge their existing beliefs and biases. They understand the value of diverse perspectives and are diligent in considering alternative viewpoints. This practice helps them avoid the echo chamber effect and confirmation bias, leading to more accurate and nuanced forecasts.

We really do not know what we don’t know. A danger of hiring people who are like you is that you artificially put yourself into an environment where diverse perspectives are not present.

Summary

Market knowledge is something that requires hard work. Opportunity lives where it’s not obvious, and we have developed mechanisms that make us believe that we know more than we actually do.

The fact that every industry deals with individual problems further complicates the issue.

Questioning our own biases and developing a toolset that allows us to find knowledge, even if we do not know yet what we do not know, is the key.

You cannot be a great leader for anyone if you do not have a good idea of what the destination looks like that you and your team are heading into.

Gain focussed knowledge that matters → Market

Separate the illusion of knowledge from fact → Knowledge

What’s next?

That’s it for the first part of this 5 part series on this Leadership guide; stay subscribed if you want to be notified about the next one in the series

Thorough Market Knowledge (This article)

Growing in front of your employees (coming soon)

Experimentation skill to learn, not succeed (coming soon)

Thanks for sharing! Lots of great advice!

One point that jumps out for me is the importance of continuing to talk to customers, no matter your level. I have seen it too many times where leaders don’t allocate time and it ends up hurting their understanding of the customer.

Great leaders get out of the building!