Leah's Product Market Fit Guide 2.0

How to find it, product-led.

Hi, my name is Leah Tharin (LinkedIn) and this is my Substack: hot takes on product-led growth/sales and organizational scaling.

I consult with companies on how to not burn everything down in the process.

Check out my Maven course to learn with me: https://maven.com/leah-tharin/productledgrowth

Table of contents

What is product-market fit?

1.1 Product-led Market Fit

1.2 Why no framework can guarantee success

1.3 Why advising (finding) around product-market fit is expensive

1.4 How to measure it

1.5 Common misunderstandings around PMFWhat does product-market fit look like?

2.1 Retention and tractionHow to find product-market fit

3.1 Ideal Customer Profiles

3.2 Tools to find it: Quantitative tools

3.3 Tools to find it: Qualitative data

3.4 Connecting quantitative and qualitative data: Outcome-driven InnovationPMF first, scale second? The product-led Scaling shift

3 Behaviors that will get you in trouble after PMF

Summary

Contributions and further reading

1. What is product-market fit?

Product-market fit is an elaborate synonym for how much your users love your product and whether the market for it is big enough. In other words:

“Are the market and product conditions in place for your business to grow?”

Lack of product-market fit is by far and the way the most common reason for startups to fail.

A common proxy for this stage is to get from the “Seed” Stage to “Series A”. Less than 10% of companies make it. (Source: VentureBeat)

It is a tablestake concept to understand in the creation of products (especially in product-led organizations). It remains crucial through all stages of a companies lifecycle. Once you found it, you have to defend it.

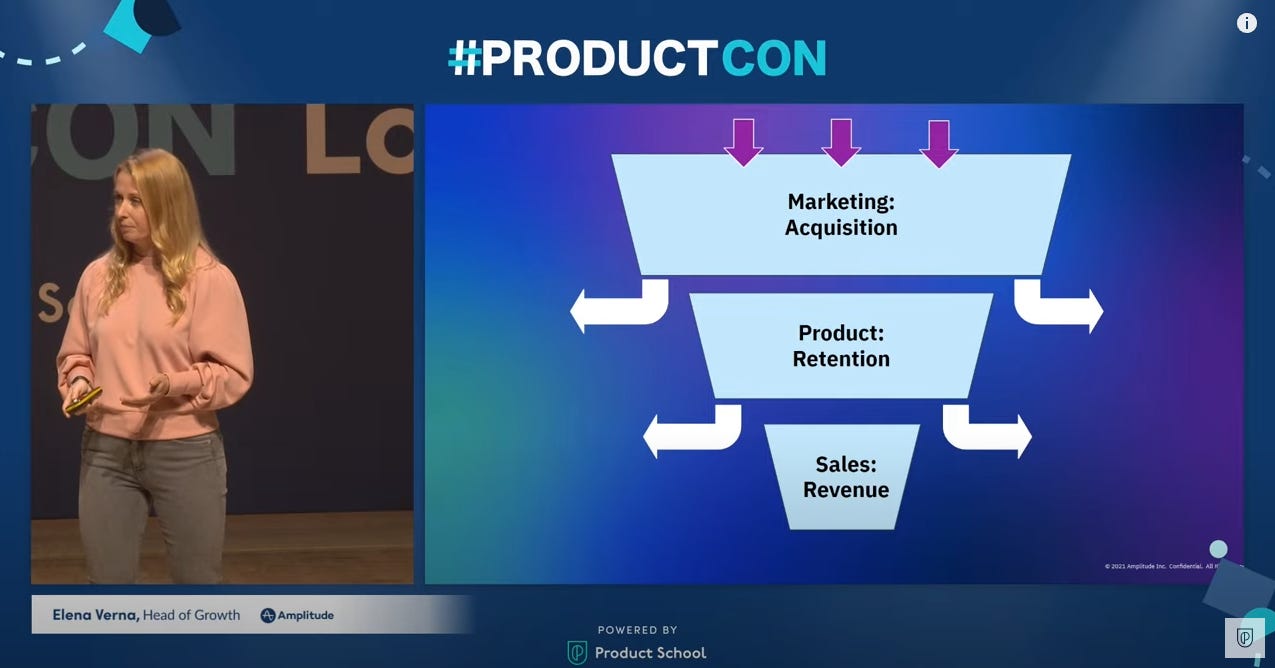

Without having product-market-fit you can never go past a certain size in your business because the rate of customers that you start to lose at some point becomes bigger than what you can acquire in the same time frame.

A good metaphor to remember is a bucket with holes in it. You wouldn’t fill it up without fixing the holes first.

“Funnels are leaky buckets”

Elena Verna, ProductCon 2022

PMF (product market fit) is best understood in the concept of a loop instead of a funnel. Users that love your product will acquire new users.

The essential question to frame around is, for every new user we acquire, how many do they acquire for us?

This is especially true for product-led businesses where we try to commercialize products by trusting them to drive most of the acquisition effort.

“Product market fit is the prerequisite for sustainable growth and the most challenging area for driving growth. It means that your product is a ‘must-have’ for people who try it and that they represent a large enough market to achieve your growth ambitions.”

Sean Ellis, gopractice.io, Author ‘Hacking Growth’

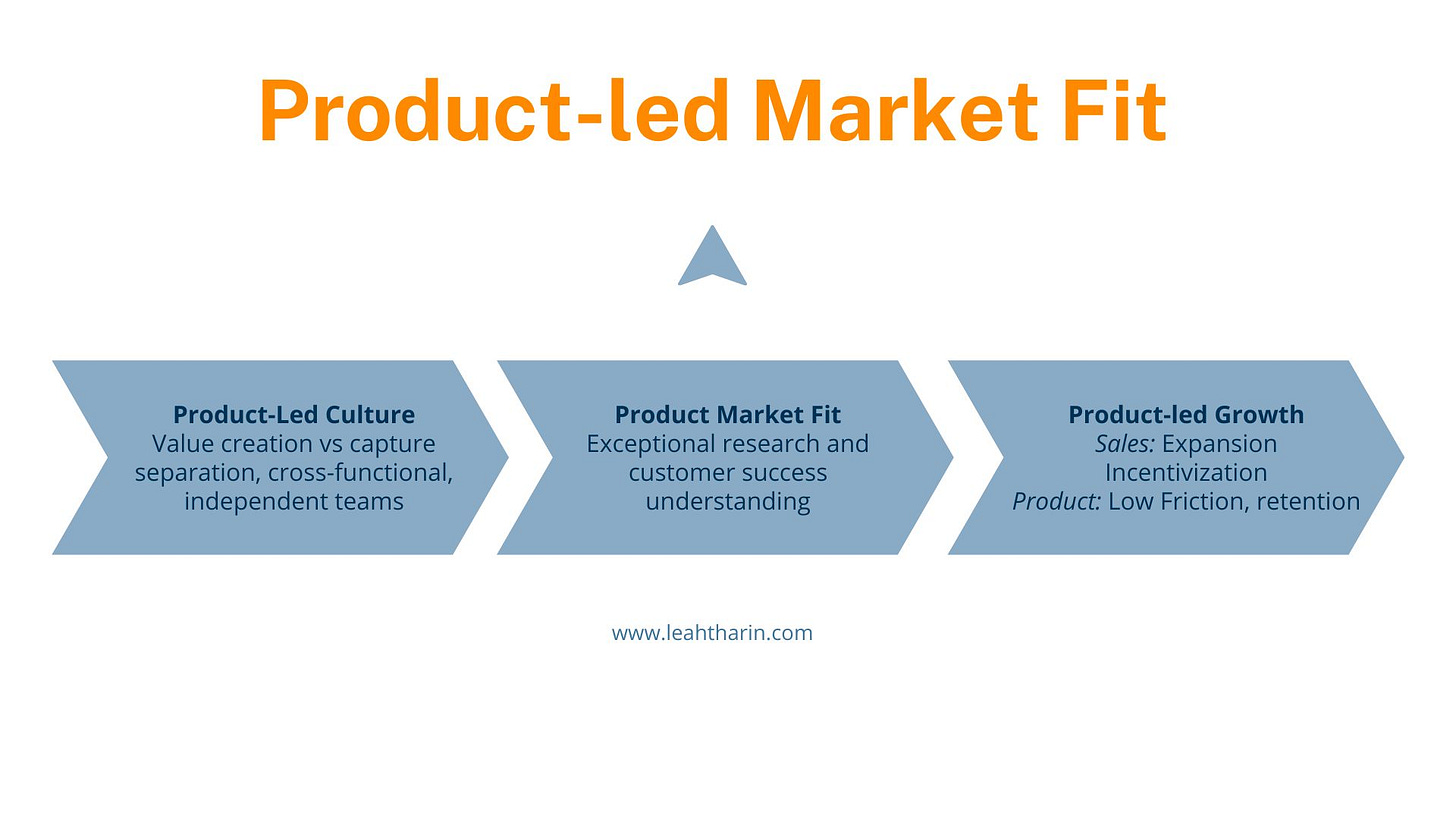

1.1. Product-led Market Fit

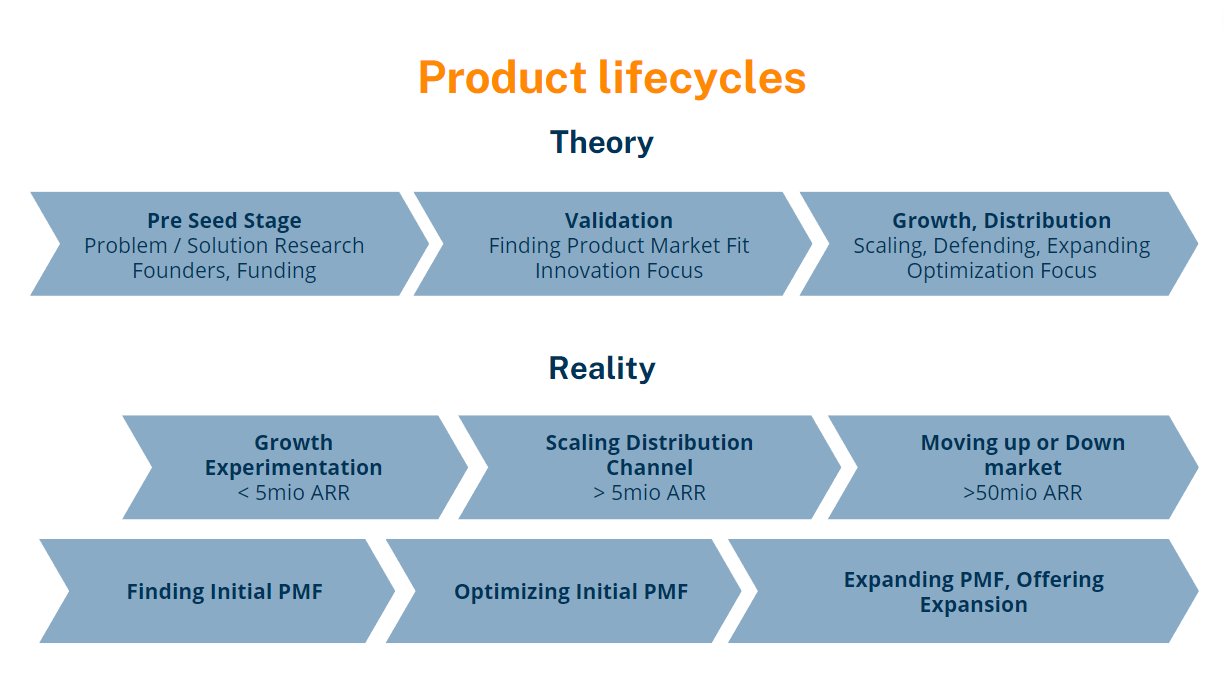

In theory, we separate product-market-fit and distribution as consecutive steps. Find PMF, then scale.

In reality, these two are inseparable and have to be run in parallel. We cannot just wait for product market fit and then start to figure out how to sell our product. Especially with a product that requires any touch (sales).

I’m calling this product-led market fit. Finding product-market fit with a product-led organization and distribution strategy in mind. This doesn’t mean that you should scale early, it means that you can already experiment with some distribution tactics.

1.1.1 Have a plan

The reason why I advocate and specialized in my career in bringing product-led growth to companies (a distribution model) is that it has the lowest risk at scale and can actually help you find product-market fit.

Building the foundations to maximize the chance to find product-market fit goes hand in hand with what you need to scale afterward with product-led growth. That is not necessarily the case for classical sales-led businesses.

Sales-led businesses oftentimes (not all of them!) stumbled into their product-market fit or relied on the product sense of a key founder.

While that makes for romantic stories it’s not repeatable and arguably also not a sustainable way to derisk a company.

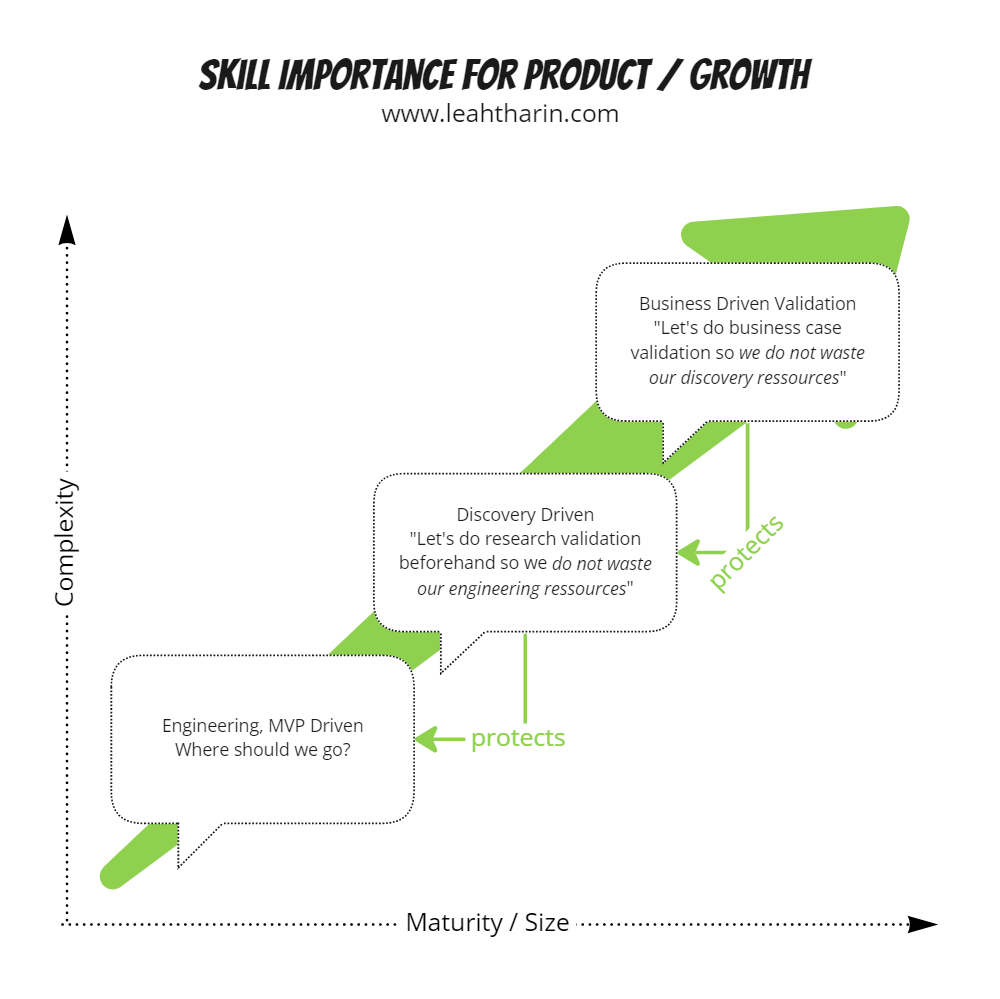

The best serial entrepreneurs which keep nailing product-market fit (even the best still fail often) have in common:

They have perfected the art to understand their customers, through the company culture and organizational structure

They have an intimate understanding of how to tell a story around it and bring the understanding to the rest of their company, all the time

They know when to build. When to research. When to do business cases

They know that finding product-market fit takes a long time. They plan accordingly with their runways and financial reserves (2y+ is not uncommon)

1.2. Why no framework can guarantee success

There are numerous frameworks around finding product-market fit. They are good and bad at the same time. They are good in that they can work. They are bad at the same time in that formalizing any of it is highly situative.

For instance, it depends on what you are trying to find a product-market fit for.

We can categorize the existing frameworks into 3 categories:

Waterfall: We think long and hard about what the customers want, build it in isolation, and then hope for the best when we release it into the market.

Agile / Lean: We build an MVP (Minimum Viable Product) as quickly as possible, copy existing mechanisms from others, and hope to learn from real customers as quickly as possible.

Qualitative business case evaluation: Instead of building an MVP we invest heavily in qualitative research and business case evaluation before we expose anything to customers.

Everybody in tech has their favorite for all of it because they saw it work once. It’s usually a toss-up between Lean and going overboard with a qualitative business case evaluation.

The real problem starts as we need to take into account to whom we are selling to. This dramatically changes how you can find product-market fit:

B2C and SaaS distribution models have access to huge amounts of data and make it relatively easy to get someone for interviews. But they live in commoditized markets so the demand for having not just PMF but excellent PMF becomes even higher. The competition is fierce and the LTV (Lifetime Value) per individual customer is typically the lowest.

Leveraging quantitative data is much easier as a result - the more downmarket (towards B2C) you go the more is available.

B2B buyers are having subcategories and complicate it all further:

Low B2B segment: When is a person part of a B2B Microbusiness, and when are they a B2C buyer? When do they buy your product for the use case, and when does it change into a team use case?

Enterprise: Enterprise buyers evaluate product-market fit not only on whether you solve their problem (usually unit economics heavy) but whether you stay long enough around to be trusted as a partner. They are inherently inflexible when it comes to changing products. How sustainable and stable your product and company is becoming part of product-market fit.

But this often means that access to quantitative data is sparse at best.Buyer and user personas: “But how do you treat the buyer and the user when finding product-market fit?” You don’t. The concept overstayed its welcome a long time ago. We now need to understand how teams and modern company structures work.

Design for a “team” and chances are you gain access to enterprise buyers.

Ok. We know there are 3 different approaches and multiple different business type complications. So which one of the approaches is the best?

All of them. I cannot stress enough how important it is to understand when which process is the correct one:

Sometimes, a waterfall approach is the correct one. Sometimes building an MVP is the best way. Sometimes we should get ourselves knee-deep into qualitative validation and business cases.

The reality is that founders and entrepreneurs take what worked in the past best for them and discount other methods too much.

I’m trying to offer a mindset to understand what’s behind product-market fit with methods that worked for me in this guide rather than a one-size-fits-all approach.

You should be equipped to understand when to use what and with which tools you have the highest chance of success. Quantitative or Qualitative.

1.3. Why advising (finding) around product-market fit is expensive

Contrary to scaling and optimizing existing processes it’s impossible to guarantee success when assisting businesses with PMF.

It can be a long arduous process and chances are most businesses will still fail despite your help. A great advisor can reduce the chance of failing considerably. But due to the lack of simple metrics to measure and business performance being something on a scale rather than a binary thing the decision to carry on is ultimately a very elusive one.

We often say “Do things that scale, not hacks”. In the context of finding product-market fit the inverse is true. Whatever gets you the key insights goes.

Whether you use Google ads to test out specific value propositions or do some really weird hacks you learned in other gigs… once you know, you know.

This essentially means that domain experience and straight-up decades of experience in the space are more valuable than in growth roles for instance.

Advising at this scale for finding initial product-market fit vs. big innovation gigs in established companies is inherently evaluated on potential value. We charge in relation to the value we can bring, not the time spent.

However: The goal of advising is often not to find product-market-fit directly but to empower internal stakeholders to recognize and find it.

The (hourly) price for that is very high. You can deduct from this that the expected skill spread of any one (or a team) needs to be quite high and success rates are low overall.

In other words: there’s almost no competition out there from others because so few can do it well.

Just remember: Don’t try to outsource the finding of product-market fit but get someone that helps you find it yourself.

1.4. How to measure it

I used something like the Sean Ellis test throughout my career to have a more objective measure of whether PMF (Product-Market-Fit) has been reached.

While the exact number is not that important Sean Ellis recommends at least having 40% of people who respond say they are “Very Disappointed” if you would take the product away.

Product-market fit is not a “metric” for your product but your individual, separate individual customer profiles. Your offering has a different PMF for each of those!

Whatever metric you use to determine whether you have product-market fit, at best those are still only indicators. Until you really have customers stick to you like crazy and go overboard with praise you probably don’t have it. Regardless of what your surveys say.

1.5 Common misunderstandings around PMF

PMF is also a statement about your ICPs, not your product

Product-market fit is different for each segment of your users. Some love it more, some less. For guiding operational decisions it makes sense to know exactly for whom you create your product best and then look closely at those users instead of the entire user base uniformly.

Of course, you can create a PMF measurement for your overall user base. The stupid thing about isolated measurements is that they cannot be compared with anything internally.

NPS (Net promoter score) is not a substitute for PMF

I’m open about why I think that the NPS is a bad metric in general. It’s also not a good substitute for knowing about product market fit since people who are detractors remove themselves anyway from your survey over time.

Any metric that is shiny but doesn’t create easier operational decisions is useless.

You might already have it but not see it

You might already have PMF with some of your users but not notice it because you can’t identify them. A common reason for this is that you acquired too many users that don’t matter to your business while the ones that love your stuff are now hidden in the overall statistic

Forgetting about it once it’s found

Product Market Fit is not limited to the early stages of a company. While it’s true that the most difficult part is to find it you still have to defend it.

Markets develop constantly and while broader user needs only shift very slowly if at all, the solutions to address them develop around you and improve.

For instance, the underlying need for people to go from place to place has not changed. At some point, horses were a great solution to this need but as we advanced cars, bicycles, etc have taken over.

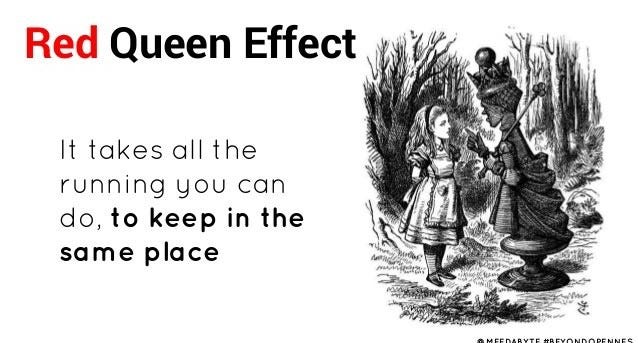

If you have to use all your resources just to maintain your position, your business is in danger. This is what we call the Red Queen Effect.

2. What does product-market fit look like?

2.1. Retention and traction

Having enough sustainable business traction means having an underlying product-market fit. The potential traction is a result of the value you create minus your value capture (we introduce friction with the customer through monetization).

Business Traction: The momentum of a company. Revenue growth, reduced cost per customer, amount of paying customers, etc. are all indicators of business traction. With some businesses, it can also be more soft factors like awards or glowing reviews in the press.

There is no product-market fit (if you agree that commercial success has to happen) without monetization and keeping it in balance is an important balance to maintain.

Retention

It looks like retention. The number of times our users come back and use it again in a given timeframe. It’s very common to lose most users relatively fast in the beginning after signup. The proof is in the pudding down the line.

Brian Balfour’s visualization is among the clearest ones:

A common timeframe to look at is 8 weeks like the product benchmark below from Mixpanel. How many % of users are coming back after their first sign up for instance:

The Problem with any benchmark metric is to know what is truly good. Unfortunately, the answer is “it depends”. As products become more focused and niche-focused so do their potential performances.

A good general rule is that some metrics are so awful that you at least know for sure when you don’t have it.

3. How to find product-market fit

The loop to improve and find a sustainable product can be broken into 3 substeps. If the overall input (value proposition) and output (monetization) are good enough it’s very likely you found product-market fit because you increase continuously the number of people who love your product.

Important: The following loop is best found per ICP, it’s harder to proof for your overall audience if you mix them up.

Proof of Value Proposition

Proof of Value Experience

Proof of Monetization

In general, it takes longer than you might assume. An often-cited number is 18 months. Obviously, it depends on the niche, industry, and other factors but the key takeaway here is that it takes longer than you think.

3.1. Ideal customer profiles (ICP)

An ICP (Ideal Customer Profile) is a profile of users that are the best fit for your product. They retain the best and pay the best. You want as many of them as possible. They are the primary users we develop the product for in a product-led business.

Unfortunately, they sometimes get lost in the noise if you spray and pray with your acquisition methods as is very common for many startups. Especially in those cases, PMF is understood best as a metric that you have to find for a group rather than your entire user base.

Your retention might look something like this:

Retention for all of your users after 8 weeks: 5%

Retention for ICP 1 subgroup after 8 weeks: 20%

Retention for ICP 2 subgroup after 8 Weeks: 3%

Depending on how you defined your ICP you just uncovered that your product is an awful fit for the 2nd group but a much better fit for the first group.

This gives you now the opportunity to focus on ICP 1 (and scale only that) or evaluate what went wrong with ICP 2.

Further reading: B2B ICP profiles in SaaS by breyta.io

3.2 Tools to find PMF: Quantitative Data

If you are already in the fortunate position to have some users you can search for groups of users that retain far better than the rest. If you find out what units them (i.e. their use cases, other commonalities) you might have found a candidate for an ICP.

It is important to note though that whatever that profile looks like… it needs to be reachable (through your means of distribution) and scaleable (a big enough market). Identifying that your family members are retaining extremely well is not an ICP. You can reach them but cannot acquire more of them.

3.2.1. Paid ads testing

Paid advertising is for most players in the market a nonscaleable tool of acquisition. For instance, you simply can’t compete in the market of CRMs against the big players and their bids.

But you can use it as a clever tool to quickly do research on value propositions:

Create landing pages with different value propositions

Run a limited ad budget with those value propositions

Capture and track the data on your click-through rate but also connect it to the number of people who clicked on a call to action on the landing page. (For instance “Sign up” or “Launch Demo”)

You should be able to answer the question of how many users you can roughly convert with which messaging to “try” the product. If you do this for different propositions they become comparable.

The use of this method is not necessarily to find out how many people you can get per $ with paid advertising. It shows you in a simple way how pressing the problem is for users in connection to your messaging.

If you cannot convert anyone with your message you don’t need to build a tool for it.

3.2.2. Say no to NPS, Say yes to the CES

Most companies are employing customer satisfaction metrics like an NPS (Net promoter score). It's a measure of how likely a customer would recommend a product to another person. The higher you score the better.

"NPS: How likely would you recommend this product on a scale from 1 - 10 ?"

Simple but not actionable:

If you have a very high NPS score among your customers this will tell you whether they love your product but not exactly what they like or dislike about it. It's still somewhat good to measure as it is a lagging indicator of churn.

There is a scenario where your NPS is high but customers still have obvious gripes with your products that you don't know about. It can suggest a false sense of security

I love my headphones (would score high in NPS) but I hate how they slide off my head constantly.

Companies have a reflex to use abstract data models to figure out what people have in common which churned. Which features did they use, and where do they come from, while this is ok it sometimes can overcomplicate things unnecessarily.

Before you even try to make sense of complex behaviors like this make sure you have a simpler, more direct way of asking your customers.

The qualitative feedback that comes from NPS surveys is nevertheless extremely valuable! My gripe is with the resulting score

3.2.2.1 Customer Effort Score - How easy was this for you?

The Customer Effort Score is not a replacement for the weaknesses of the NPS but it is arguably a better tool to grind away and surface weaknesses of your product.

Every product is a collection of features. Spotify not only plays music but also has playlists, and podcasts, suggests new music, can create parties with your friends, donate to artists, manage your account, like and dislike music, and so forth.

Instead of asking how likely would you recommend Spotify to a friend, we can ask customers on the web specifically about features at the moment when they just used them with a CES (Customer Effort Score) survey:

"You just shared a song with a friend, how easy was that from 1 - 5 (5 being very easy)? "

Any user that answers this question will be ready to tell you if your feature sucks even though they might still love your overall product.

If you do this for all of your important features you get comparable results on which parts of your product need improvements, where you have big chunks of 1 rating, or whether people are just indifferent to it.

Features with low average scores are detrimental to your product and might need rethinking as they push customers potentially to other solutions.

Notice how the question is phrased "How easy was this for you" is based on the assumption that things that come easy to us are perceived as having great value, or non-obstructing in what we try to achieve.

3 Steps to implement it

The CES is best asked right after a success happened with a tool. A download, something was saved, do NOT interrupt the flow of the user before they complete the action.

Since the CES is triggered on a feature level you need to be careful not to trigger it too much. I recommend asking it not more than once per 30 days/user but this depends on your product and might even be way too much for high-usage products.

A comment field is optional. Filling out the CES as well, do not force users to answer it. Makes it easy to dismiss (x) and capture "ESC" as a hotkey and click outside of it.

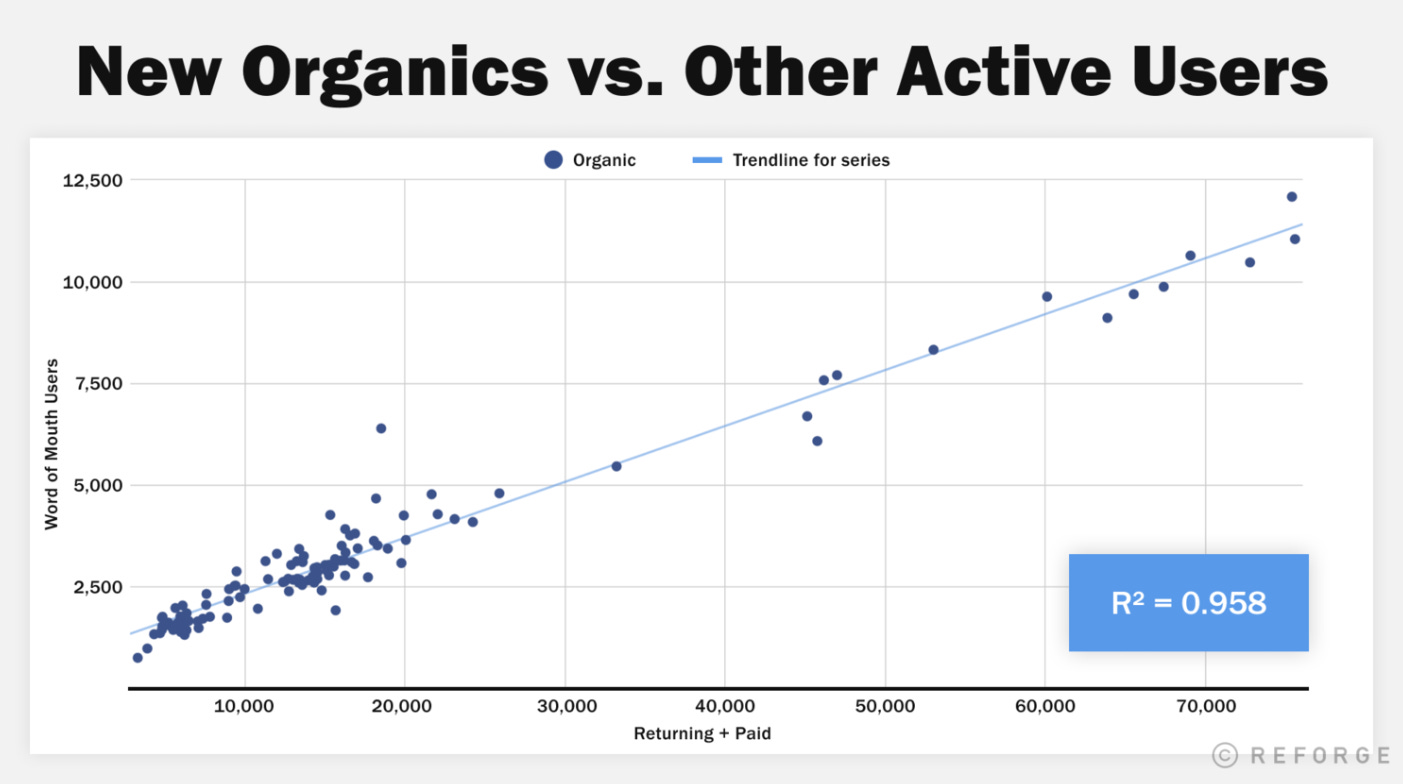

3.2.4 Word of Mouth Coefficient

For product-led businesses, Word of Mouth is a fantastic thing to index. Not only does it serve for acquiring more users it also is an indicator of whether users love your product → An indicator of product-market fit.

The most formalized measurement of it I know of has been written out by Yousouf Bhaijee:

The amount of New Organic Users divided by (Returning Users + Non-Organice New Users) is giving you a Word of Mouth coefficient.

So what’s a good coefficient? It depends. I’m careful with benchmark metrics in this case, however:

It’s a stable metric that you can monitor, the more you increase it the more likely you move towards product-market fit. You do need a certain amount of data and users to leverage it though.

3.3 Tools to find it: Qualitative Data

While there are many qualitative interview techniques I found in the case of product-market fit that it’s very easy to waste your time with the wrong ones.

Whatever you use:

We focus on past realities and do not ask hypothetical questions about the future.

3.3.1. Focus on Reality - Switch Interviewing

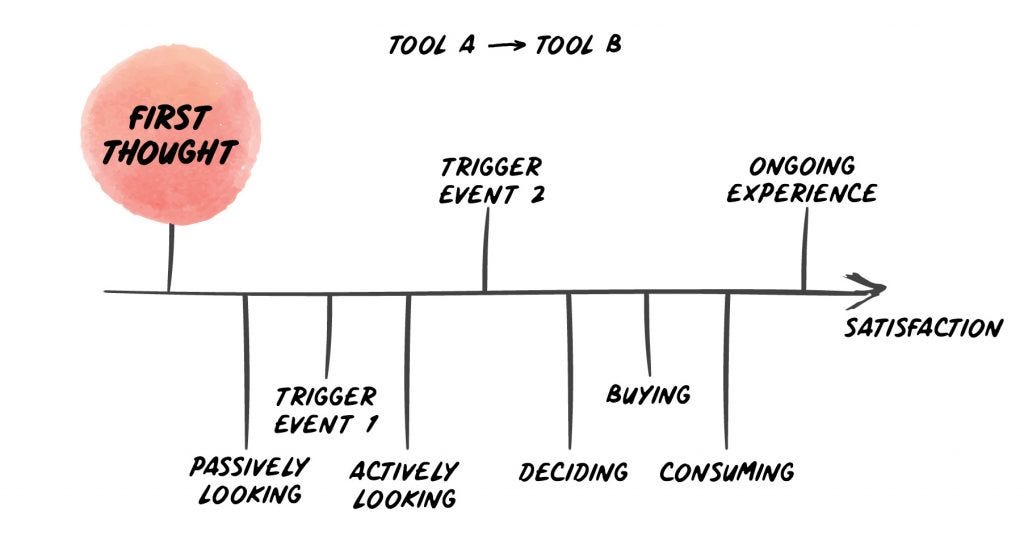

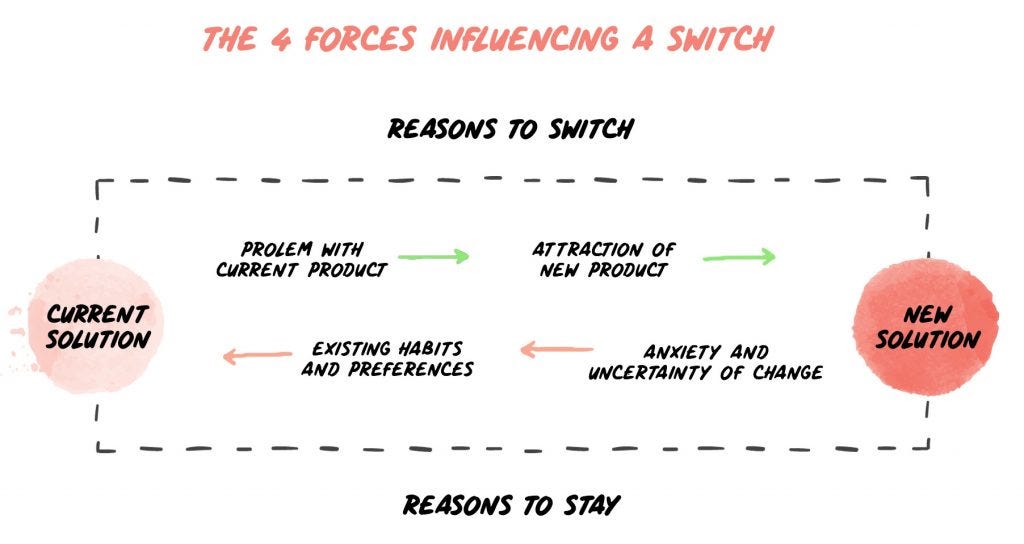

Switch interviews are a technique used in qualitative research where we ask people about buying decisions they did in the past. It turns out that these decisions are usually multi-layered and complex contrary to what we thought.

"I had a friend a couple of years ago that bought a tesla roadster. Pretty cool car, I was impressed, and while I didn't want one for myself, that was the first time I saw one up close."

The customer is aware of your product, but they're not yet buying a new car, maybe they are happy enough with the one they have. We call those in the "passive search" phase.

"Last year my car broke down and I had to bring it in for an expensive service, I had a replacement vehicle that was purely electric and I figured, hey let's use that for a couple of days, I was quite surprised how well the car ran and how strong it was compared to my other one!"

This particular person had an opportunity to test out an electric car and has now much more subjective experience to compare it to their existing car, also because their current one just had an expensive service they might be closer to replacing their car at some point and if they do we consider them to be in the "active search" phase. If they find something that matches their needs they are ready to switch to a new product.

This example illustrates that buying decisions are complex and start usually much earlier than we anticipate or even recall. In interviews like this, you will hear various reasons, and some of them get repeated more often than others, but it is rarely just a simple comparison of two things.

The difference to classical market research is that these things did happen. People are unreliable in predicting what their behavior will be leading to wrong data, but they are quite accurate in recounting what did happen.

For instance:

"We notice in interviews that having a friend who owns an electric car and talks positively about it is a big factor in whether a customer made the switch from a gasoline to an electric car."

Armed with that knowledge you could now build better recommendation features, making it easier for owners of electric cars to share their experiences and so forth.

Switch Interviews are an important qualitative tool to uncover hidden needs you were not aware of.

3.4 Connecting quantitative and qualitative data: Outcome-driven Innovation

If we are enabled to surface qualitative and quantitative insights we can start to connect them. A great way to do this is Outcome-Driven Innovation (ODI). The framework is coined originally by Tony Ulwick. It draws in some form what the Kano Model does but in a more scaleable way.

We have hundreds of needs associated with the markets we address and one fundamental problem that we deal with is twofold:

Which particular aspect of the problem should we address specifically?

How do different groups of our potential users feel about them before we build them?

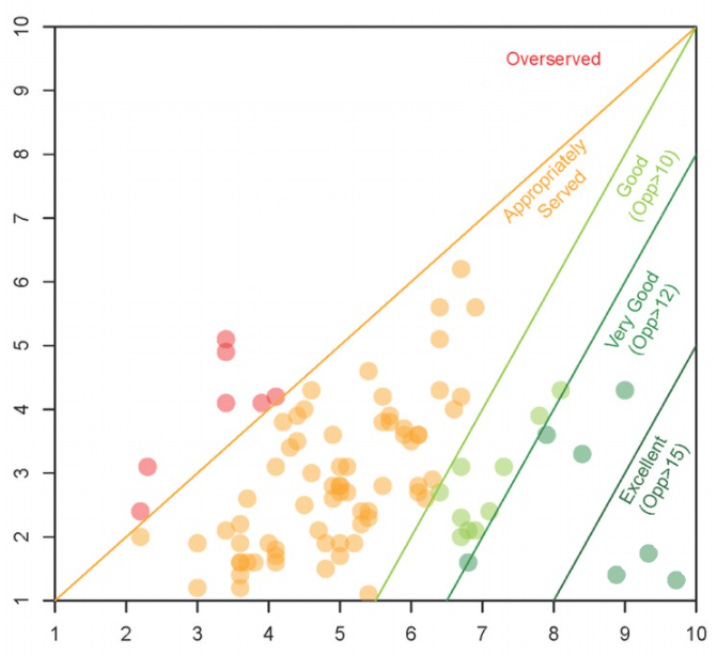

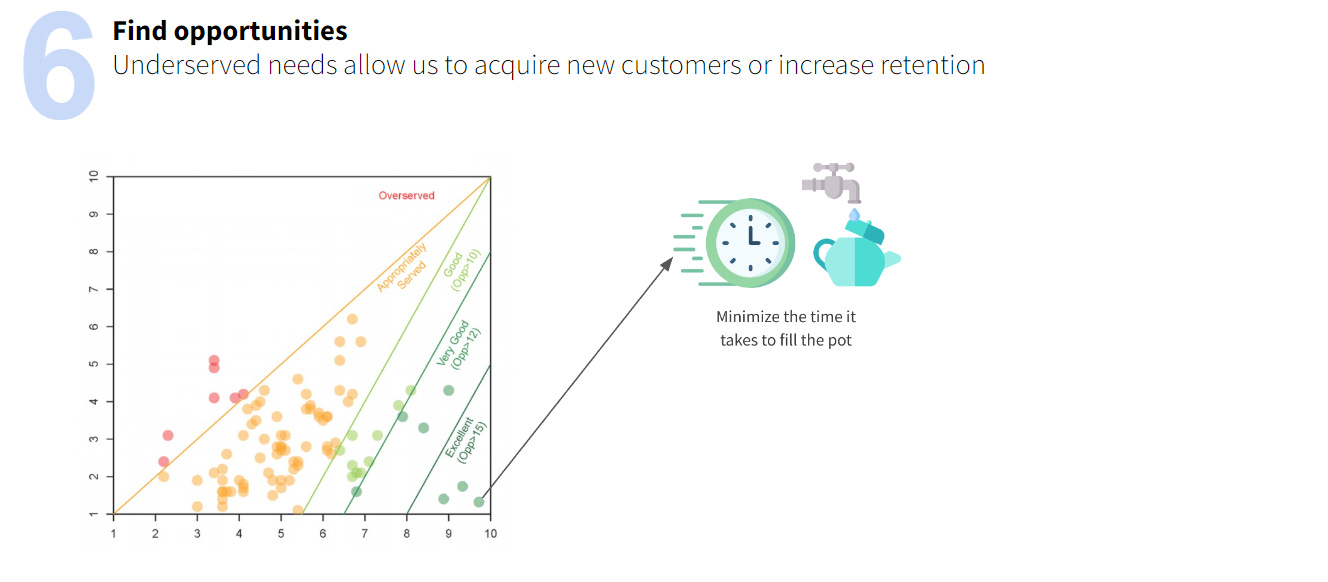

The ultimate output is something like this:

An ODI opportunity map sorts the needs by how “under” or “overserved” they are.

In other words, it evaluates a crucial aspect of product-market fit (acquisition and retention) on a micro level. If done right this leads to extremely actionable areas to execute on for product teams:

On the most basic level, every one of these dots represents a “need”.

For instance “I need to minimize the time it takes to fill a tea pot”

These are typical needs that are associated with the overall Job of a business that serves a market with “I want to drink tea”. It could be a producer of teapots. A tea producer, kitchen appliance supplier for big chains… or a subscription service for the most exquisite teas online.

Depending on where the spot lands you know whether it’s worth it to focus on or not.

Here’s the simplified process to get there in 7 steps:

3.4.1. Find the Job / Market

Identify the market you are participating in. If you already have an existing product this is usually simple and clear.

For example “I want to drink tea”.

If you have an existing product and are unsure exactly what people are using it for - ask them. Interview them. (See qualitative interviewing)

3.4.2 Map the Job

We understand what “steps” are necessary for a user to get their job done. A simplification to 6 steps is a good starting point.

3.4.3 Find quantifiable Needs for each Job Step

Almost everything we do can be condensed into a quantifiable statement that tells us whether we think it’s successful:

“Fill a teapot with water”

The faster it fills the better

The easier it is to fill it the better

The better the quality of the water the better

We can formalize these statements into “Maximize / Minimize” statements

“The faster it fills the better” → “Minimize the time it takes to fill the pot”

“The easier it is to fill it the better” → “Minimize the effort to put the pot under the tap”

“The better the quality of the water the better” → “Maximize the quality of the water”

A good number to limit yourself to is to identify 20 needs per job step.

Important: Do not just “think” these up. You should utilize qualitative customer interviews to understand how those customers “evaluate” success with their tools. Typical statements are “I love how quiet it is!” “It really annoys me how I cannot find my documents”

Good research surfaces about 100 of these needs per step, then you consolidate and simplify them together. This happens quite fast with a dedicated research team.

3.4.4 Validate Statements on a specific customer group

Here’s where we deviate from classical market research. We will ask specific customer groups questions (in a survey) based on the needs we identified in 2 dimensions.

Typical groups::

Existing users of our platform → This informs you about risks in your product, opportunities to reduce churn

Customers we don’t serve yet, in the example the “I need to drink tea”: → Finding PMF, PMF Expansion

Cooks

Homestay Parents

Dimensions:

How important is something to you on a scale of 1 to 5

I.e. When you fill a pot with water, how important is it to you that you are able to

“Minimize the time it takes to fill it”

“Minimize the effort to put the pot under water”

How satisfied are you with your current ability/tool on a scale of 1 to 5

I.e. When using your current kitchen to fill a pot with water, how satisfied are you with your ability to:

“Minimize the time it takes to fill it”

“Minimize the effort to put the pot under water”

Why?

Classical research makes 2 mistakes in trying to get a grip on what’s important to your customers. They ask about hypothetical situations and they ignore the dimension on how well customers are already solving their jobs.

The latter part is extremely important. You might find that the job of “finding information on the internet” is very important to people. So you start a new startup imitating Google.

Even if you provide the same quality of search results and technological execution you might still fail. The reason is that your users are already having a good solution with Google.

Unless your solution is significantly better than what the users use you have no opportunity to execute on. This is what we call an opportunity gap.

You can either, fulfill an existing underserved need that annoys people now. Or you surface a new need your users didn’t realize can be satisfied (new category creation)

Size to get meaningful results:

In my experience, you want to have at least ~200 answers per question to get meaningful results to account for variance.

Strategyn’s whitepaper suggests even between 300 and 800 answers.

3.4.5 Visualize results - bringing them together

Now we bring them together. If you used the same survey with different groups (cooks vs, private households vs. gardeners) you get comparable opportunity maps per ICP (Ideal Customer Profile).

We create an average of answers on the 2 dimensions we evaluated:

Importance

Satisfaction

Each dot represents one “Need” (How important is it to you… / How well can you..) NOT individual answers

3.4.6. Evaluate - Find Opportunities

Analyzing the results is now quite simple. The more to the bottom right (the more important and less served) something is, the closer you should look at it:

If you asked your existing users: These are the needs that you underserve. The moment they find a competitor that does it better they will churn.

If you asked new potential users: These needs are underserved in the market. You know exactly what kind of qualities you need to address.

If all your results are somewhere in the middle and hard to distinguish then you didn’t ask a specific enough group.

3.4.7 Leverage Insights

Product: Develop a solution that addresses those underserved needs.

Product and Growth: Target key results that positively influence those needs

Marketing: Use targetted messaging to address underserved needs specifically

3.4.8 Further Reading - ODI

Getting this process right is hard work. It requires sensible interviews and customer insights but has so far been the most formalized approach I’m aware of. It makes opportunities comparable and creates alignment. Great for finding PMF and PMF Expansions.

It creates quantifiable proof for elusive customer needs and which direction to run into. And even if you cannot drive the entire process through you end up with valuable customer insights either way.

The goal is to get actionable goals for your product teams that inch you closer.

Read More: The Strategyn Whitepaper on ODI goes into much more detail and a more elaborate process.

4. First PMF, then Scaling? The product-led Scaling shift

It might be true to assume that you are building for the same customer over time when you achieve product-market fit and start to get a grip on the market, but scaling what got you here doesn’t always work, even if it’s in a big enough market and your pipeline looks healthy.

We should not look at our customer base as a homogenous group that exerts the same buying and usage behavior, even if they are having the same problems as each other to solve.

A common concept (first coined by books like “Crossing the Chasm”) divides our markets roughly into early adopters and the majority of the market. And in between is the famous “chasm” that’s so hard to cross between the two.

The usually given explanations for that are:

"Early adopters don't care about price or the quality that much, they need bleeding edge features, the newest stuff."

"For the Early Majority, you need to focus on the quality, unit economics (and therefore price) and a broader feature coverage"

While true, that leaves out an important to understand the difference between the two: their behavior to acquire solutions

Early adopters and their behavior

Early adopters are not only a small portion of your market. They *behave* differently in how they shop and acquire products.

They not only want different features they also seek out new solutions actively. And that can go through all segments of B2B too. You have a CMO in a big corp on the bleeding edge of Martech, trying to level up their org. They are early adopters.

And they will actively search for new solutions. That's why you can put a perfect distribution focus to the side at the beginning and focus on creating a great product. Prove that you can retain them first, and you're off to the races.

In other words, focus on the product like a maniac first. Do not let go of this search for product-market fit until you have it.

The party is over. Hangover is here

Suddenly trying to address more of the same aka "scaling" means the party stops. We have to deal with things that are painful at scale:

Legal

Bloated Infrastructure

Geographical friction (culture, language, local competition, etc.)

HR problems

Thrashing

Defending existing growth

This is especially relevant for ANY product-led business. Shifting gears from PMF to GTM will hurt.

It's not your competition. It's whether you can stop your organization from breaking down while you try to build your product suddenly for a majority that's looking for a sustainable, stable solution.

But all you did so far was to innovate and ship ship ship. Now is the time to evaluate, slow down, and sometimes even unship.

And for that, you need to expand what you understand under "product". It's including the post and pre-experience, not your features.

Behaviors that get startups into trouble

Let’s look at 4 typical behaviors that get companies into trouble:

1. Triggering “scaling” because of wrong signals

We commonly talk about product-market fit in the context of having an efficient motion of acquiring and retaining users and turning them into customers. This needs to happen in a big enough market and this motion has to be also repeatable.

A common advice in this regard is that once you “have” product-market fit you should now transition into being a scale-up.

In other words, load up on VC money or if you’re fortunate enough to be bootstrapped, cash positive you start to hire more people other than the core team to run the show.

The way that I saw this play out is that founders oftentimes understand this phrase as do one, then do the next thing, and forget about the first thing while scaling.

First of all, you’re never done with product-market fit. It becomes at best a health metric that you cannot degrade with whatever you do. The best leading indicator that your product-market fit is going to deteriorate is customer success through customer signals we can objectively measure. And there, quantitative actions such as “how many documents are being processed per user” beat surface surveys like NPS which never tell you the full story.

In either case, at some point, you will decide that it’s time to scale. And ideally, this is when you have this aforementioned efficiency. What happens in reality? Founders either massage the numbers because they cannot wait to tell everyone they have product-market fit or they overindex on what’s happening at a competitor and think they have to catch up.

This can get hurt or even kill your business really badly. If you scale by hiring more people without being efficient enough you artificially shorten your runway for an inefficient motion requiring more and more people to plug the holes of an inefficient bucket.

2. “What got us here will get us there.”

I’ve been there myself. What gave us success in the past is comforting and we hold on to it. After all, I just said that we should scale scalable things. Unfortunately, this means that you start to scale things that cannot be scaled.

Typical examples are organizational structures that work for 20 people but burn with 50. If you’ve never scaled a company you will learn it through a trial by fire or by getting someone in that does know how to do it.

A typical one for PLG companies is that they think what got them to 5mio ARR is bringing them to 50. There are plenty of examples of really nice products that made it to 5mio ARR just by way of the product itself…

…but at some point, you have to think about distribution differently. Maybe even have sales. And just giving someone a sales title for a classical B2C product is definitely not going to cut it.

Connected to that is thinking that just releasing more features (even if they have a good fit) will in some way accelerate your growth. That’s rarely the case, you need to learn how to talk in the market about them.

3. “Small team handling majority distribution

This is connected with the other two points but you cannot underestimate what it takes to prepare a company to distribute the product into a majority market. You have to be very mindful of what matters to them but more importantly, you have a new problem to worry about that was maybe not as apparent as before:

You need to defend your existing growth when you try out new things. Changing the pricing of the product might mess with existing plans, or raise some eyebrows in sales.

Sunsetting features might have a good impact on your new customer acquisition but will slowly drive away your existing base. This requires a lot of tracking and processes that are costly but necessary.

How do we make sure that we proactively think and see about signals before they hit us? We cannot react to declining revenue, that’s too slow.

PMF first, scale second?

That’s why I struggle with this notion that it’s first pmf and then scale. The story is more complicated than that, you need to maintain and scale the processes that ensured you found it in the first place.

5. Summary

What it is?

”Product-market Fit means being in a good market with a product that can satisfy that market.”, Marc Andreessen

What does it look like?

It looks like retention. People don’t stop using your product.

How to find it?

A toolset that combines quantitative and qualitative data is invaluable. Whatever brings results, goes.

6. Contributions and further study

Sean Ellis

Sean Ellis, Author of “Hacking Growth” and mainstay name in the product world. He has a simulator with his gopractice initiative it covers PMF and learning data-driven product growth.

Michael Seibel, Ycombinator

One of the best Storytellers on the topic is Michael Seibel, Director and Group Partner at Y Combinator. The Y combinator blog in general is a great resource and Michaels's experience as a series investor is second to none:

https://www.ycombinator.com/library/5z-the-real-product-market-fit

Marc Andreessen

Marc Andreesen’s most foundational post on the topic is a must-read for anyone

Seems that the link to switch interview is not valid anymore. This one might be correct: https://thoughtbot.com/playbook/rapid-product-validation/switch-interviews

Your work on measuring PMF (and why NPS is a bullshit metric) 🤣 has been pivotal in my understanding of PMF. Thanks, Leah Tharin! 🥰