Should you Product-led Growth?

It’s not a question of if, but when. Market theory, but cool.

People come to me expecting a quick fix whenever the topic of PLG (Product-led Growth) comes up like I’m PLGandalf with a magic wand. But sorry, “You Shall PLG” isn’t the answer.

Here’s the deal—PLG isn’t just a buzzword. It’s a survival strategy and a nuanced one at that. Things aren’t binary. You don’t simply decide “Yes, we’ll do PLG” or “No, we won’t do PLG” – you create a strategy that takes into account where you are now and where you’re headed and how far you delve into self-serving your product.

But one thing is certain: if you stick to old ways and don’t evolve when it comes to your PLG strategy, the market will soon leave you behind.

Let’s dive into when PLG and self-serving matters, what drives successful product positioning, and how to make the shift before you get disrupted.

Understanding PLG and Engagement Models

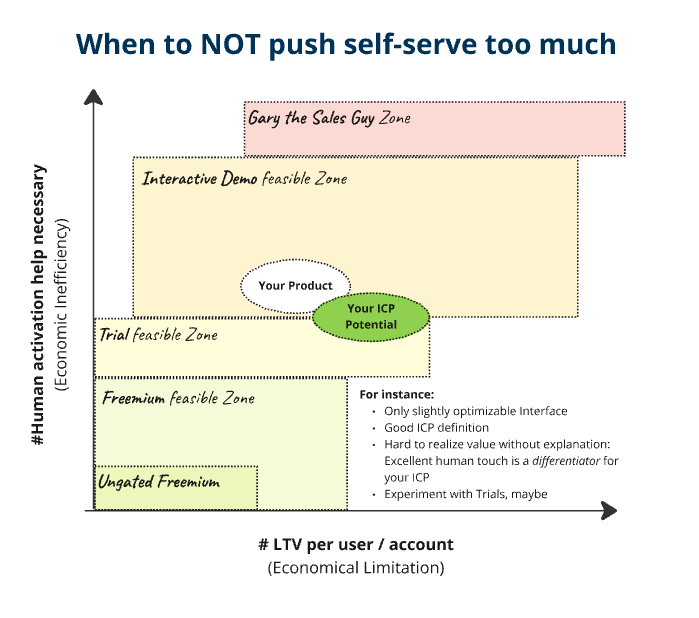

Before diving into PLG, know where your Ideal customer profiles stand with your product. Consider the lifetime value (LTV) of your users and the human activation energy needed to onboard them. This is important - don’t just skip this section - if you don’t fully understand what’s happening in this chart, the rest of this essay won’t blow your mind like I know it can ;)

The higher the lifetime value (LTV) is per user, the more likely your product is complicated and needs Gary the Sales Guy to hand-hold the customer through the buying process. If the product wasn’t complicated, someone will sooner or later undercut you by offering a simple Trial for customers with a lower price point.

Understanding this balance helps you decide which engagement models to use. Most companies are using some or even all of these. But we can think simplified that each Ideal Customer Profile (ICP) you have prefers a specific start of an activation journey.

Let’s quickly define each activation lever you have at your disposal:

1. Gary the Sales Guy (High-Touch Sales)

Good ol’ Gary the Sales Guy represents the high-touch end, where extensive human activation is necessary due to the complexity and high LTV of the product. This approach is typical in enterprise sales, where each customer’s value justifies the resource investment. Gary’s sweet spot is at the top right of the chart, indicating high human intervention and high LTV.

Why is it that Gary does not end up on the bottom right of that chart where LTV is high and the product is extremely simple to use?

Gary is expensive (economic inefficiency)

If a product use case is simple, Gary is not needed, and a competitor will leverage that. This is where disruption happens (economic limitation)

2. Interactive Demos

Interactive demos offer a controlled, guided experience of the product, allowing potential customers to explore key features. They are quite involved and have tracking and different experiences for different user groups within your product.

While more self-serve than high-touch sales, these demos often lead to further discussions or trials to complete the conversion. Positioned just below Gary, interactive demos are ideal for complex products that need some demonstration but not full engagement to understand their value proposition.

Interactive Demos and Gary work great together; the best processes combine both; you might even see Gary use an interactive demo in a call that you can then explore yourself without a complicated setup. Most interactive demos also automatically create leads out of people who engage with them.

Another bonus is that interactive demos are commonly separate from the rest of the infrastructure and very easy to maintain and set up.

A great example is on Zendesks website: https://www.zendesk.com/demo/

3. Trials

Trials give users limited-time access to the full product, allowing them to experience its value firsthand. They require less human intervention than interactive demos, making them a more self-serve option. Trials work well for products that users need to explore on their own to understand, with the built-in time limit driving urgency but also giving enough time to derive value.

4. Freemiums

Freemiums allow ongoing access (no time limit) to the product with some limitations, encouraging users to upgrade for full features. This model requires minimal human activation, as users explore at their own pace. Positioned lower on the chart, freemiums are effective for products that offer significant value even with constraints, aiming for mass adoption and conversion over time.

Their purpose is not only to activate and convert but also to use the free users as advocates for further acquisition. If you think of Word of Mouth as a primary driver for your brand a freemium is almost always part of the answer.

5. Ungated Freemiums

Ungated freemiums eliminate all barriers, letting users access the product immediately without even requiring any form of sign-up. This model relies entirely on the product’s ability to engage users without guidance, making it the most frictionless and self-serve option.

Ideal for simple, intuitive products, ungated freemiums are at the bottom of the chart, representing low human intervention and lower initial LTV.

They are relatively rare and highly contextual but commonly hyperfocused on their ICPs and no one else. They build on the assumption that whoever is using the product already knows most of it because it copies the interface of something else.

A good example is Rows. I’ve written about it in detail in this post:

Where are you headed?

It’s important to know where your company (and it’s ICPs) falls on this chart - remember a range, not a dot - but it’s equally important to know where you should be headed.

You do not want to end up in the top left quadrant - high human touch, low lifetime value.

You do want to end up in the bottom right quadrant - low human touch, high lifetime value.

In other words, we want to maximize the ARPU (Average revenue per unit/user) while lowering our CAC (Customer Acquisition Cost)

“Thanks Leah, no duh everyone wants that. How do I get there?”

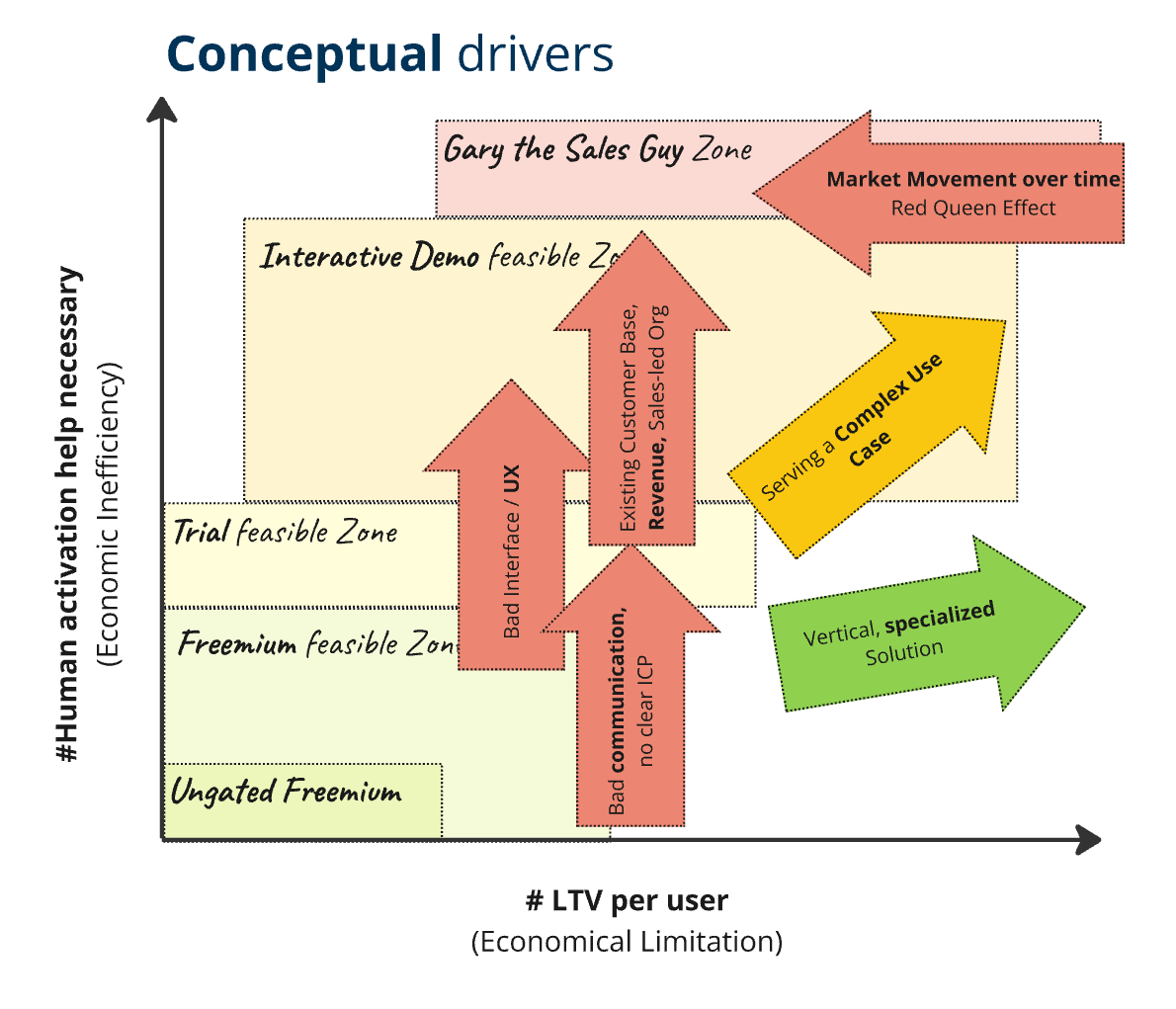

I’m getting to it! Let’s talk about the most important question you can ask yourself: What conceptual drivers have put our product where it currently is on the chart?

1. Red Arrows: Factors Pushing You Up the Chart

These are the drivers that increase the need for human activation help, making your product less economically efficient without increasing your revenue, you have to minimize the bad effect of them as much as you can, especially at scale:

Bad Interface/UX: If your product’s interface is confusing or difficult to navigate, users will require more support to understand and use it effectively. This drives your product higher on the Y-axis, increasing the need for human intervention, and making freemiums and trials less likely to be the optimal choice.

Existing Customer Base & Revenue: A large, entrenched customer base can resist changes to the product, especially if those changes affect their existing workflows. This inertia often necessitates more human involvement, keeping you higher on the chart. This is unavoidable to some degree and the reason why enterprise companies are considered to be slow.

You can only minimize the effect by having an efficient product-led product organization that measures and delivers customer-centric impact and avoids shipping anything without impact.Bad Communication & No Clear ICP: Poor communication strategies or a lack of a well-defined Ideal Customer Profile (ICP) lead to friction in the onboarding process. This misalignment often results in a need for additional support, again pushing you up the chart.

This happens when a company focuses on a market that is too big, yet before they have proven that it can acquire bigger shares of a smaller market. (Verticalization, more specialized offering)

2. Green and Yellow Arrows: Factors Pushing You to the Right

These drivers help you move to the right on the chart, increasing the LTV per user but also increasing complexity:

Serving a Complex Use Case: Products that address complex, specialized needs often have higher LTV because they provide significant value to a smaller, more targeted market. While this can require more support, it also justifies a higher price point, pushing you to the right on the chart.

Vertical, Specialized Solution: Niche products designed for specific industries or verticals can command higher prices and deliver higher LTV. These solutions cater to specialized needs, positioning your product further to the right on the economic spectrum. Commonly they also serve a more complex use case but specific to that particular industry which is by everything we know the gold standard right now

3. The Red Queen Effect: Moves you to the Left

The Red Queen Effect illustrates the tipping point of when a company cannot innovate anymore because it fell back too far behind. All it can do at that point is maintain their market shares with every little breath it has left.

As competitors innovate, technology advances and customer expectations grow, your product’s position on the chart will likely shift to the left. Without ongoing improvements, you risk being left behind, regardless of where you currently sit on the spectrum. This effect underscores the importance of staying agile and responsive to market dynamics.

In other words, if you’re not innovating for long enough no amount of effort of yours will get you out of it anymore, because it requires all your effort to just to hold on to what you have.

Growth will stop. The company is doomed to fail.

Case Study: HubSpot vs. Salesforce – A Tale of Two PLG Strategies

The journey to Product Led Growth (PLG) is not a one-size-fits-all path, and the contrasting experiences of HubSpot and Salesforce provide a compelling case study in how different approaches to PLG can lead to dramatically different outcomes.

While HubSpot successfully pivoted to a PLG model, Salesforce has faced significant challenges in making the same transition. Understanding why HubSpot succeeded where Salesforce struggled, reveals key insights into the factors that can make or break a PLG strategy.

HubSpot: A Successful PLG Pivot

In 2017, HubSpot, much like Salesforce, was heavily reliant on a sales-led approach. Their product required significant human intervention, which placed them squarely in the "Gary the Sales Guy" zone—dependent on direct sales efforts to drive customer acquisition and retention. However, HubSpot recognized the shifting market dynamics and the growing importance of self-serve models.

To adapt, HubSpot undertook a strategic simplification of its interface and began splitting its product portfolio into more modular, self-service subproducts.

This allowed them to gradually reduce the need for human activation help, enabling users to explore and adopt the product more independently depending on what they need first.

Today, HubSpot is a successfully transitioned PLG company that offers freemiums and full trial experiences and a simple-to-use product.

Their ability to scale integrations and enhance their product offerings through strategic acquisitions like Clearbit (understanding that data enrichment is an important part to a CRM) further solidified their position as a PLG acquisition leader.

HubSpot’s shift was not just about adopting new models but about fundamentally rethinking their product architecture to align with a lower-touch, higher-LTV approach.

Salesforce is still worth more (250 billion) than Hubspot (26 billion), but you can argue that Hubspot is better positioned in a market that will further become commoditized with increasing competition.

Their core product is simply too complex to compete with more vertical, specialized solutions and can’t effectively capture that value because they are easier to activate and onboard onto.

In general, these companies follow the mantra: “It’s easier to keep a customer than to acquire a new one” (retention). If they serve these smaller customers well, while they grow they are not acquirable for Salesforce.

Salesforce: The Struggle to Pivot

In contrast, Salesforce, despite recognizing the same market trends, struggled to make a similar pivot. Back in 2015, Salesforce was firmly entrenched in the "Gary the Sales Guy" zone, relying on a complex, sales-driven approach to sustain its large enterprise customer base. Several factors hindered Salesforce’s ability to transition to PLG:

Complex Interface: Salesforce’s product was deeply complex, designed for high-touch, enterprise-level customization. Simplifying this interface to make it more self-servable proved to be a significant challenge.

Entrenched Customer Base: Salesforce had an extensive and deeply entrenched customer base that was (and still is) resistant to change. These existing revenue streams made it difficult for Salesforce to justify a major overhaul of its product interface or to shift towards a self-serve model.

Sales-Led Organizational Structure: Salesforce’s organizational structure is heavily sales-driven, with a focus on direct, high-touch customer interactions. This structure makes it difficult to pivot to a model that reduces the reliance on human intervention.

Despite efforts like the acquisition of Slack and attempts to make their interface more user-friendly, by 2024, Salesforce is still struggling to move out of the interactive demo feasible zone. While they made some progress, the company remained high on the chart, where significant human activation help was still necessary to onboard and support users.

Why HubSpot Succeeded Where Salesforce Struggled

The key difference in outcomes between HubSpot and Salesforce lies in their ability to adapt their product and organizational structure to the demands of PLG:

Product Simplification: HubSpot’s success was driven by their proactive efforts to simplify their product, making it easier for users to adopt without significant hand-holding. Salesforce, on the other hand, faced the monumental challenge of simplifying a product that was inherently complex while sitting on billions of annual revenue that needed to be retained.

Market Flexibility: HubSpot was able to break its product into more modular components, allowing for a more flexible and scalable approach to PLG. Salesforce’s product was not as easily divisible, making it harder to adapt to the self-serve model.

Organizational Willingness: HubSpot’s leadership embraced the shift to PLG, reorganizing their teams and product strategies to align with this new approach. In contrast, Salesforce’s deeply ingrained sales-led culture created resistance to the changes necessary for a successful PLG pivot.

Your distribution model is not a tactic, it’s a strategy

Deciding when to adopt a PLG strategy isn’t just a tactical decision—it’s a strategic one that requires careful consideration of your product’s position, your customers’ needs, and the overall market dynamics. And it’s not a one-time decision.

By using interactive demos, trials, and freemiums at the right time—and continuously reassessing and adjusting as needed—you can enhance customer experiences and drive growth. The examples of Salesforce and HubSpot offer valuable lessons in timing your shift, but remember, even after the shift, you need to stay agile and responsive to ongoing changes.

With a phased approach and a deep understanding of your audience, you can confidently answer the question, “When do I do PLG?”—not just today, but every day.

When you HAVE to do more self-serve

This chart highlights a critical issue faced by many companies: the risk of being disrupted by more agile competitors who effectively leverage product-led growth (PLG).

The chart shows a "Dangerous Gap" between where your product currently sits—likely in the interactive demo feasible zone, requiring significant human activation help—and where your Ideal Customer Profile (ICP) potential lies, closer to the trial or freemium zones with higher lifetime value (LTV) and lower human intervention.

The "Dangerous Gap" represents the missed opportunity to make your product more self-servable. This gap is particularly risky because it leaves room for competitors who can offer a similar product with less friction, potentially attracting your customers away. If your product could be self-servable but isn't, you risk falling behind as the market shifts towards more PLG-oriented models.

You need to recognize this gap and take action before it’s too late, avoiding the fate of being disrupted by a more nimble competitor who understands the power of PLG allowing them to sell more cost-efficient into the same market

Example: When AI came into the market for companies that offered “customer support call centers,” their entire market moved to the bottom left with their existing solutions because AI suddenly became almost overnight better at their job. You can now get well-functioning support coverage without ever having to talk to someone who sells you an entire call center. You can simply try out and buy a product like Intercom and do it yourself.

In that case, the need for human touch has decreased, and with it, the LTV per user/account that uses it. If you want to sell a support solution in 2024, you’re almost forced to offer a freemium / trial unless you serve a highly specialized industry or vertical that an AI model can’t serve.

Transition Strategy to Self-serve

The second chart presents a clear strategy for closing the "Dangerous Gap" and transitioning your product toward a more effective PLG model. This transition is outlined in two stages:

Stage 1: Learning to Self-Serve with Friction

The first stage involves understanding how to make your product more self-serving while managing the inevitable friction that comes with change. This requires adjustments in several areas:Compensation Plan Adjustment: Incentives need to be aligned with the new PLG goals, ensuring that the sales team is motivated to support the transition.

Product Team Reorganization: Shifting focus from feature development to outcome-driven development is key. Teams must be restructured to prioritize customer outcomes over simply adding new features.

Outcome-Driven Development: The focus should be on creating a product experience that delivers clear value with minimal human intervention.

Stage 2: Moving to Freemiums

Once your product has successfully navigated through trials and gathered sufficient data, the next step is to introduce a freemium model. The learnings from Stage 1 are crucial here:Structuring Freemiums: Use the insights and data from trials to design a freemium model that resonates with your ICP, offering enough value to engage users while encouraging upgrades into higher subscription tiers.

Optimizing Team Activation: Self-serving an individual use case is one thing, but understanding what activates a team and what drives their activations as a collective is the secret key in many B2B companies since we deal with teams, not individuals.

Product-Led Sales Support: Even within a freemium model, some level of sales support may be necessary, particularly for guiding high-value users toward premium tiers. We need to learn how to pull these accounts “out” of the group at the right time so we can proactively contact them. (Lead timing and generation)

By following this two-stage transition strategy, your product can move from a vulnerable position at risk of disruption to a stronger, more competitive stance within the PLG framework. This approach not only enhances the customer experience but also drives higher LTV with less reliance on costly human intervention.

When you should NOT do too much self-serve

Freemium models can be powerful tools in a product-led growth (PLG) strategy, but they are not always the right choice. The decision to use freemiums must be carefully considered, especially when certain conditions suggest that other models, such as trials or high-touch sales, may be more effective to be the starting points.

The graph here provides a visual guide to understanding when freemiums might not be the best approach.

Key Factors That Limit the Usefulness of Going Too Far self-serve (Freemiums, etc.)

Only slightly Optimizable Interface

If your product's interface is only slightly optimizable for the use case it covers, meaning it requires substantial user guidance to navigate effectively, a freemium model might not deliver the desired results. In these cases, users may struggle to realize the value of your product on their own, leading to high churn rates or low conversion from free to paid plans. Freemiums work best when users can quickly grasp the product’s value without extensive onboarding.

Value cannot be understud without explanation (new category, too early)

If the differentiation of your product hinges on a nuanced understanding of features that are difficult to convey through a self-serve model, you may need to rely more on trials or interactive demos that allow for more guided exploration.

This can happen when you try to bring a new solution in a market that simply doesn’t understand yet what they would expect of it. The problem here is that these people do not understand what they could gain regardless of their product. If a user doesn’t even have an idea what a product is for they also won’t be able to explore it by themselves.

Differentiators outside of self-serve value

If excellent customer support or a high level of service is a key differentiator for your ICP, freemiums might undersell your product’s true strengths. In such cases, trials with some level of guided support (Superhuman does this excellent) may provide a better experience, allowing users to fully appreciate the product’s capabilities while also not driving your cost through the roof. (Less people sign up for trials than for freemiums, but they also have higher intent → lower CAC)

Conclusion: The Strategic Choice Against Freemiums

Freemiums are not a universal solution. When your product requires significant human intervention to showcase its value, or when the product’s strengths are tied to features that are not immediately apparent without support, other models like trials or high-touch sales processes should be considered. By understanding the limitations of freemiums and recognizing when they are not suitable, you can better align your PLG strategy with your product’s unique characteristics and your customer’s needs.

Summary

The reality of whether you should do PLG or not is a misnomer quite often. Most companies mix and match approaches from product-led growth and sales-led models. The question is how far you should push into the self-serve zone without overdoing it:

If you don’t do it, and you should, you get disrupted.

If you do it, and you shouldn’t, you’ll wreck your unit economics.

The reality for most companies I’ve engaged with, though, is the first. Especially established companies are coming from a market that was simply not built for PLG models in the past. The market has moved on since then and having at least a good mix between self-serve and sales is nowadays expected and not just a nice to have.

Want to learn more with me live? Upcoming cohort courses with me:

Product-led Growth in B2B in October 2024

How to find your Ideal Customer Profile in B2B SaaS in September 2024

Never written here before. Great piece specially the PLG + Product offer Divisibility as a Strategy, it made some thoughts come into place . Thanks Leah

Tremendous overview and dead on.